Is tax-aware long/short just a shiny object?

Serious doubt from several sizable investment managers

Tax-aware long/short strategies are white hot

Tax-aware long/short strategies, like the 130/30 and 250/150, are growing like crazy.

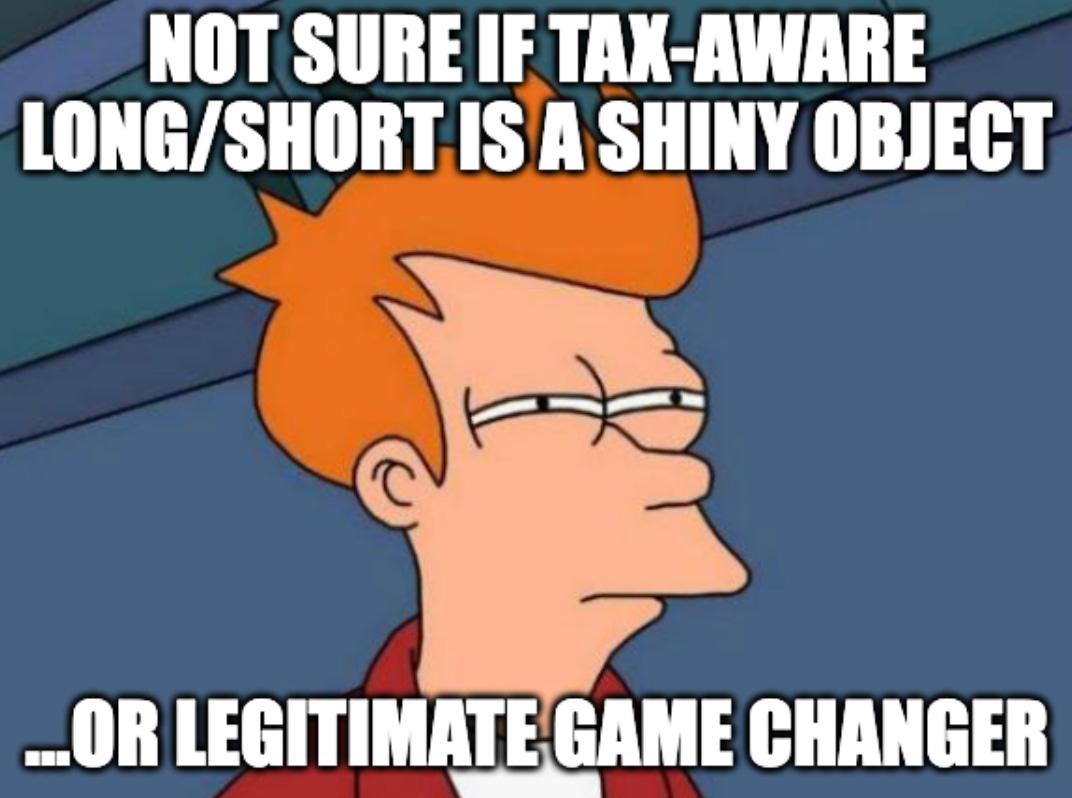

The two largest investment managers offering these strategies, AQR and Quantinno, each manage more than $13 billion AUM in this strategy, and continue growing rapidly.

My posts about long/short are consistently my most read, and it’s the #1 thing advisers want to discuss with me (aside from, or sometimes in combination with, Section 351 conversion).

This article will get you up to speed on tax-aware long/short.

Is this hype?

I can’t say for sure, but these are the things that advisers (who may, admittedly, be enamored with the new shiny thing) tell me:

“I would re-custody my client assets [usually to Fidelity] to get access to tax-aware long/short”

“I use tax-aware long/short to win new business” (and, humorously/paradoxically, “clients don’t get it”)

“It solves so many use cases [single-stock concentration, locked-up portfolios, already-realized capital gains, etc.] that it’s worth having around.”

You get the point.

But that’s not the whole story.

Critique

Several folks running large investment management practices are not investing in tax-aware long/short strategies, and I wanted to print their comments too.

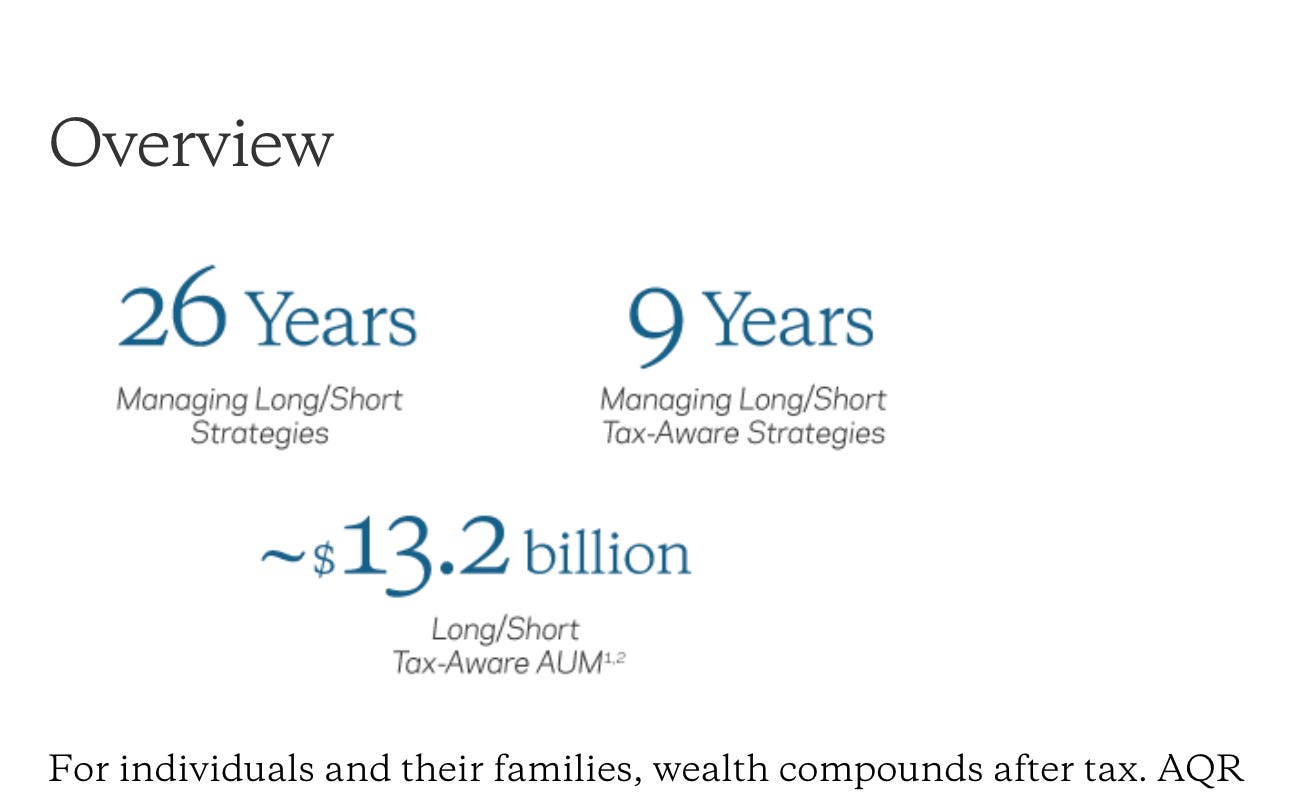

The quantitative critique is in the lower right of the image above, which shows that a hypothetical investor with only long-term capital gains, is better off post-liquidation by simply using a standard long-only approach (the cost of closing the shorts, which are taxed as short-term capital gains, is expensive, according to the article).

I don’t have the original source for this (uh PowerPoint?) slide, but it reflects the conclusions in a paper BlackRock/Aperio published last fall.

Tax-aware long/short is a powerful strategy when an investor expects to realize a lot of short-term capital gains and needs losses to offset them.

The critique is that it simply isn’t an everyday use case.

Not enough, anyway, for the managers I’ve spoken with to warrant reallocating staff toward a build or even a partnership (even without a build, there’s always cost to train sales folks, deliver reports, market the new thing, plus the opportunity cost of moving staff to new tasks, etc.).

Other critiques include:

Pretax alpha could be, uh, negative

Tracking error is typically higher than an indexing strategy

They are 1.5x-5x more expensive than other SMA strategies

Long/short presents unique portfolio risks (e.g., short squeeze, etc.)

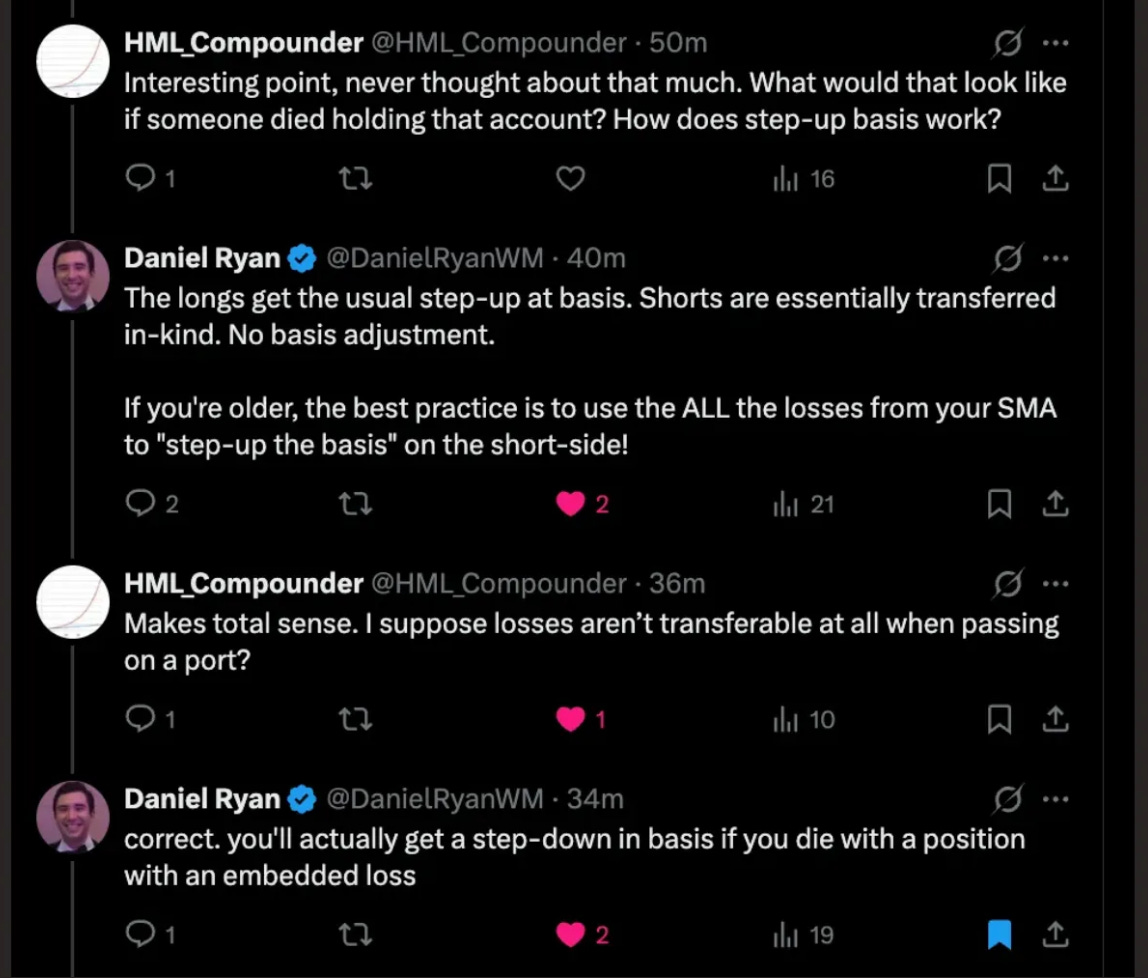

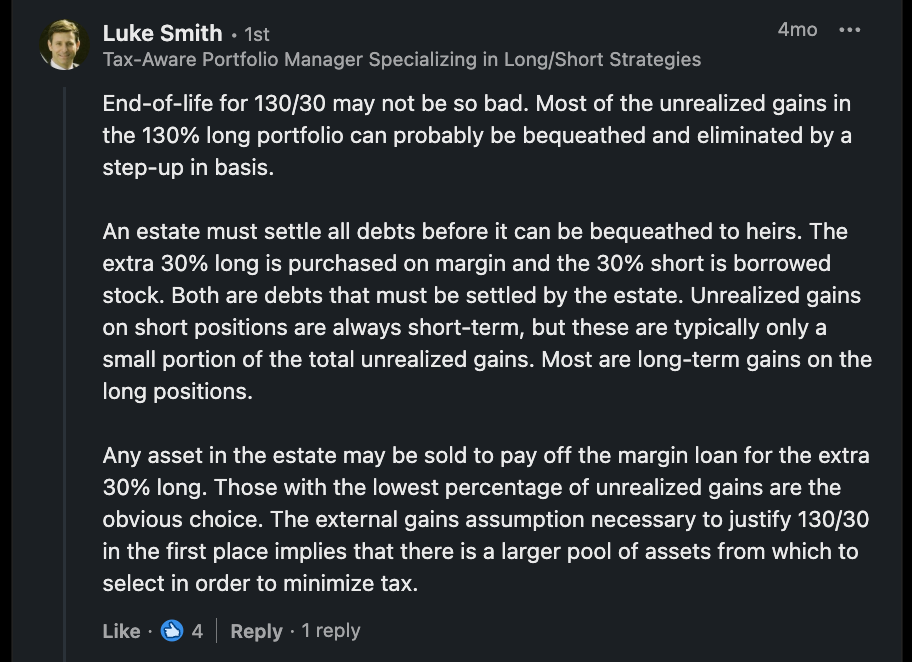

Investors must settle all debts (leverage and shorts) at death (plus, there’s no step-up on shorts)

This is a weekday note, so I’ll just tease a deeper topic.

Isn’t settling all debts expensive?

Suffice it to say the following. At death:

Longs get stepped-up basis (gains erased)

Shorts don’t. No adjustment (gain/loss preserved)

Settling all debts is the on-your-heels/reactive approach, so most managers transition the portfolios to long-only in anticipation of death.

So, while investors can’t bequeath shorts, and debts/leverage must be settled, the separate account wrapper grants investors the flexibility to pay the debts using any (e.g., high-basis) assets they choose, which makes the blow a little lighter.

More on this another time.

Common or edgy?

Tax-aware long/short solves more problems than offsetting short-term capital gains, including single-stock diversification and already-realized capital gains (especially early in the calendar year), reanimating locked-up separate accounts, and probably more.

Are these edge cases or common use cases?

If they’re edgy, adding them to an existing business does not make sense, hence the skepticism of several managers I’ve spoken with. If they’re common, how common? Are these strategies a powerful foot in the door? What is that worth? Now we’re in ROI land, rather than full-stop land.

I don’t have the answers, but will follow up when I learn more.